The Rise of the Universities

As students at a university, you are part of a great tradition. Consider the words you use: campus, tuition, classes, courses, lectures, faculty, students, administration, chancellor, dean, professor, sophomore, junior, senior, fees, assignments, laboratory, dormitory, requirements, prerequisites, examinations, texts, grades, convocation, graduation, commencement, procession, diploma, alumni association, donations, and so forth. These are the language of the university, and they are all derived from Latin, almost unchanged from their medieval origins. The organization of this university, its activities and its traditions, are continuations of a barroom brawl that took place in Paris almost 800 years ago.

CAROLINGIAN EDUCATIONAL REFORMS

Charlemagne (d. 814) realized that his empire needed a body of educated people if it was to survive, and he turned to the Church as the only source of such education. He issued a decretal that every cathedral and monastery was to establish a school to provide a free education to every boy who had the intelligence and the perseverance to follow a demanding course of study. Since the aim was to create a large body of educated priests upon which both the empire and local communities could draw for leadership, girls were ignored. Charlemagne died, civil wars broke out, and the attacks of the Magyars, Vikings, and Saracens began before his plan could be carried out.

CATHEDRAL AND MONASTERY SCHOOLS

Some schools had been established, however, and continued through the worst of the times that followed. Their object was to train priests, and their curriculum was designed to do that and little more. The course of study consisted of two parts, the grammar school in which the trivium (the “three-part curriculum,” from which our word “trivial” is derived), consisting of grammar, rhetoric, and logic. Grammar trained the student to read, write, and speak Latin, the universal language of the European educated classes; rhetoric taught the art of public speaking and served as an introduction to literature; and logic provided means of demonstrating the validity of propositions, as well as serving as an introduction to the quadrivium (the “four-part curriculum’) of arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music.

Arithmetic served as the basis for quantitative reasoning; geometry for architecture, surveying, and calculating measurements – all essential to managing a church's property and income. Astronomy was necessary for calculating the date of Easter, predicting eclipses, and marking the passing of the seasons. For some time, about all the cathedral and monastery schools could manage was to train enough priests to provide the bare essential of educated local leaders.

By the 1000's, this began to change as some schools began to develop elements of their quadrivium beyond the requirements of mere priestly training. Some integrated their curricula by adopting a standard text such as The Consolation of Philosophy by Boethius, or some other compendium of knowledge, the most famous being those written by Cassidorus, Martianus Capella, or Isidore of Seville. The masters at some other schools developed a more flexible approach to the concept of education and attempted to extend knowledge as well as impart it to their students.

One of the latter was the cathedral school of Reims, where the Spanish-trained Gerbert of Aurillac developed the mathematical aspects of the quadrivium by introducing Arabic numerical notation, the use of the abacus for numerical calculation, and the astrolabe for astronomical observation. Under the leadership of one of Gerbert's students, the nearby monastery school of Fleury continued this development. Other schools developed in different directions, with Orleans specializing in classical studies, and Chartres in the mathematical theory of music. Still another such center of specialized learning was the little Norman monastery of Bec, which, under the leadership of Lanfranc, and Anselm, became known throughout northern Europe for the teaching of Law.

GREGORY VII AND THE GREAT REVIVAL OF LEARNING

Most textbooks discuss Pope Gregory VII only in relation to the Investiture Controversy, but he was very important in the history of the university. In 1079, he issued a papal decree ordering all cathedrals and major monasteries to establish schools for the training of clergy. The result was a great expansion of education, and some places in which there were a number of monasteries concentrated, became centers of education. Nowhere was this more true that in Paris.

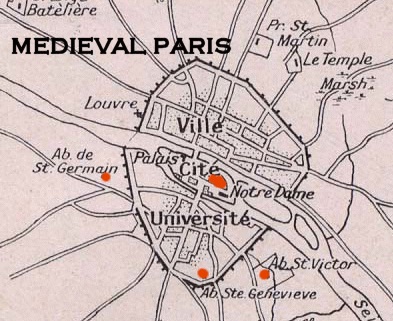

PARIS

Medieval Paris was dominated by the cathedral of Notre Dame and the royal palace facing it on the Ile de la Cite, the island in the Seine that formed the heart of the city. Notre Dame was the residence of the archbishop’s executive secretary, the chancellor, who had the sole power to issue the licenses necessary to preach and/or teach in the diocese. Naturally, the cathedral and surrounding buildings housed and impressive number of teachers and students attached to the cathedral school. The royal palace, across the square from the cathedral, was the center from which the provost of the city worked. Leading his own police force, the provost was the royal deputy charged with running the city. Since the king and archbishop had more important affairs, the provost and chancellor were the heads of the secular and ecclesiastical government of Paris, and generally worked together rather closely.

On the left bank of the Seine, there were several monasteries, each with its own school: Ste. Genevieve, St. Germain des Pres, and St. Victor. Although each of these schools had a master, he was not the only teacher there, as had been the case in many of the earlier cathedral and monastery schools. Qualified teachers could apply to the chancellor or an abbot for membership in their institutions and, having been granted that membership, they formed part of the faculty of that institution’s school. Some instructors resided in the monastery itself and some outside, providing the basis for a distinction that persists in the professor and associate professor. The professors hired assistants (assistant professors), who might someday become professors themselves, while particularly able students might be hired to teach basic subjects in the grammar school as instructors. The professors usually offered a course, or series, of lectures in which they would read from a text, a work generally accepted as being important to know, so the students could copy down the words, and then the lecturer would offer explanations of the text, while the students made notes in the wide margins they had left for that purpose (marginalia). As an aside, it was customary for notes referring to other works relevant to the passage to be put at the bottom, of foot, of the page, a practice that has survived as the modern footnote. When the course of lectures was competed, the student would have finished copying the text and his notes of the lecturer's commentaries in his textbook. When the student felt ready he could appear before the chancellor to be examined. If approved, he was given a diploma, an official document that permitted him to preach or teach in the diocese of Paris.

Students could attend any courses they wished from any of the faculty in any of these schools, since all that really counted was whether they could satisfy the chancellor that they were competent. So they tended to find rooms in the district of the city between these centers and to pick and choose which lectures they wished to hear on which books. The instructors began to rent halls in the district in which to give their lectures, and this part of Paris became a center of learning, being known as the Latin Quarter, since the common language for the various people living and studying there was Latin. The cathedral school of Notre Dame was the home base of the most respected and well known teachers, and at first overshadowed the schools of the Latin Quarter but that began to change. The chancellor of Notre Dame considered the fact that all teachers (and all students, too) were in "holy orders," that is, they were clergy although neither priests nor monks. As the representative of the bishop, the chancellor felt that all clergy in Paris owed him obedience and tried to tell the instructors not only what to teach, but how they were to teach it.

This clash between the chancellor and masters was only the beginning of a tension that continues to the present day. Just as the chancellor of Notre Dame claimed the power to command the obedience of the masters in all things because they were members of the Church, so too in many state universities today, chancellors or presidents attempt to extend their authority over the faculty because the faculty are state employees. In medieval Paris, this conflict caused many masters (instructors) to move to the Latin Quarter and join the “faculties” of the monastery schools there. The intellectual center of the city moved to an area further from the chancellor’s direct control, and the masters began to consider the chancellor as an enemy rather than their administrative head.

NEW MOVEMENTS IN THE LATIN QUARTER

By the early 1100's there was great intellectual ferment in the Latin Quarter. Translations into Latin of Aristotle's Greek logical works were arriving from translation centers in Spain and Sicily, and the scholars of Paris found themselves with powerful new tools of reason. Peter Abelard, a student in the Latin Quarter who had returned to become a master in the school of Notre Dame, set both students and masters on their ears with his book entitled Sic et non (Yes and No), in which he demonstrated that the accepted authorities that everyone had been studying contradicted one another on almost every basic point that one could think of. He concluded that one had to collect the opinions of the authorities, but use logic to determine which of these opinions were correct.

The manner of teaching soon changed. Instead of listening to their master read and interpret, the students wanted to be taught how to reason. The public debate soon replaced the lecture in attracting the student’s attention. They particularly like to hear their masters debate each other. At the same time that the nobles were developing the man-to-man armed confrontations of the tournament, scholars were developing the logical combat of the public debate.

At the same time, the demand of both Church and princes for trained administrators and lawyers was growing, and students found that skill in argumentation was a surer key to success than being able to determine the date of Easter or explain the mathematical proportions that were harmonic and those that were not. An ex-student by the name of John of Salisbury, commented that the study of the Liberal Arts (the trivium and quadrivium) were being abandoned in favor of mere professional training.

THE BIRTH OF THE UNIVERSITY

One day in the Autumn of 1200, a German student decided to throw a bit of a party in his apartment for some of his friends and sent his servant, a ten- year old boy, down to the corner tavern to get his large wine-jug filled. The tavern owner gave the boy sour wine and, when the boy complained, the bartender and some of the barflies beat the kid up and threw him out into the street along with his broken jug. Why? I don't really know. Perhaps it was because the German emperor had stirred up the English to start a long and bloody war with France. Or maybe it was because the barkeep liked the students' money, but not the students.

In any event the boy dragged himself back to his master, and the student and his friends went down to the tavern and beat up everybody before they went home with a large jugful of decent wine. The barkeep asked the provost to punish the students, and the provost gathered his men, together with a number of volunteers, and blocked all of the streets into the Latin Quarter. They then went hunting for the German student, slapping people around as they went. A number of masters and students were irritated by this, took to the streets, and a pitched battle ensued. The provost and his men finally withdrew, but not before they had killed five students, including the German student who had started it all, and who happened to have been the prince-bishop elect of Liege (in what is now Belgium).

The chancellor refused to help the master and students of the Latin Quarter, so they barricaded the streets leading into the Latin Quarter, and the masters held a meeting that night. They decided to organize themselves into a union, or, as it was called in the Latin of the time, a universitas. Since their students were studying in order to become masters themselves, the union included the students as more or less junior members. The next day, representatives of the union went to the king of France and announced themselves as spokesmen for The University of the Masters and Students of Paris.

They demanded a number of corporate rights, privileges and protection from the king. When the king asked what they would do if he decided to say no, they replied with the famous words, “Then we shall shake the dust of the streets of Paris from the hems of our gowns.” In effect, they were threatening to leave and to do their teaching elsewhere. King Philip realized that Paris would lose much of its attractiveness and he would lose a considerable amount of taxes if the masters, students and all of the people who provided services to the Latin Quarter were to leave, and so agreed to protect the members of the Universitas. Much more happened in succeeding years. There were continuing struggles with the chancellor and provost, and even among the students and masters themselves, but in the end the union of masters and students was recognized by all. They gained powers – the right to establish the curriculum, the requirements, and the standards of accomplishment; the right to debate any subject and uphold in debate any subject; the right to choose their own members; protection from local police; the right of each member to keep his license to teach as soon as he had been admitted to full membership; and others. These rights were often won in open battles in which people – masters and students – died, but they were rights that faculty still guard jealously today.

As an aside to help you to become more knowledgeable than your fellows who don't study medieval history, I’ll tell you why graduation is called Commencement (and no, it’s not because it’s the beginning of your “real life”). In the large halls where students and faculty ate, the faculty used to eat at table on a raised platform at one end of the long line of tables at which the students sat. When the students finished their course of study and graduated, they became fully-fledged members of the University and equals of the faculty. Consequently, at the grand banquet with which they celebrated their graduation, faculty and former students (both the newly-graduated and alumni) ate together as equals. They shared tables, or, in the Latin of the time, they ate at a commensa, a common table for all. This is why, not so long ago, Commencement and Reunion took place at the same time and why the University Dinner was the high point of the graduation events.

— Lynn Harry Nelson, “The Rise of the Universities” Lectures in Medieval History [original website]